I took a quick 2 day trip to Rome to stay with my brother at the German Archaeological Institute’s villa, to explore and take note of some of Rome’s different interactive and multimedia heritage experiences, to feed into my research back in Brighton.

On the first day of the 48 hour trip, I visited The Baths of Caracalla, where my brother had told me a VR experience was available, though he had not tested any of it himself. Luckily we both possessed documentation to allow us into heritage sites for free in Rome, so this opened up a lot of potential experiences to us which could be documented.

Terme di Caracalla

The baths were spectacular monuments, and Terme di Caracalla is the first great archaeological site in Italy that has been recreated for viewing in 3D. A completely outdoor site (as is much of the archaeology in Rome), the clear skies and sunshine augmented the experience. A visitor was given the option of the 3D addition for 7 Euros extra. This consisted of a smartphone placed into a mobile plastic holder resembling the front of an Oculus-like headset, which has a small opening for sound, and a simple paddle switch on the right hand for selecting the locations on the map or starting each VR recreation (though there was GPS on the smartphone, there was a numbered map visual in the headset, where the visitor would select the number they wished to play at the correlating location, instead of triggering it through movement).

The headsets seemed popular, with a high percentage of visitors paying extra to use them (from my observation). They were offered in Italian and English, and the simple paddle design seemed to create little confusion. Personal reflections were on the basic nature of the experience – it was merely a smartphone in a plastic holder – but this did allow for mobility and it was lightweight for carrying (attached by a lanyard around your neck). The device seemed aware of you lifting it to your face or taking it away; this you merely held it to your face when you wanted it, and moved your head to position a small dot onto the desired selection, and then flicked the paddle to selections.

This experience has similarities to my own project through the use of GPS location and mobile devices to augment the heritage experience, though personal adaptations would be to the audio offered, and a more GPS accurate rendering of the visuals. For example, the audio was merely a spoken guide (a man in a toga actually appears in the room talking when the 3D rendering is present, which was a nice touch), but there is a lot more that could have been done with it. Sound effects to give a sense of the enormity of the space would have been exciting, and the addition of ambient music seems to be popular in these installations (further Roman sites visited offer this). For example, a marble slab at one end of a pool was still present (and was noted for the notches on it in the audio guide), as it was from an ancient game where visitors of the baths would try and throw walnuts or marbles into the dips for amusement. This could be an exciting opportunity for immersive sound effects; as when the audience approaches the area, the sound of walnuts hitting marble could be heard (and positioned to be coming from a location where the bathers would be for 3D effect), instead of just a guide telling you about it. Making use of footsteps on the mosaic floors would have also been an opportunity to recreate the huge room’s acoustics.

Also something to note, though the smartphone application was aware of GPS location, and aware of head rotation, there was no change in the positioning of the visitor within the rendered space when they moved forward or backwards, just an awareness of which direction they were facing. Therefore, when the 3D loaded, a visitor could be at one end or the other of the room, and they would still appear to be in the centre, with no change of perspective or depth perception. Whether this counted as true virtual reality was personally debatable, as the immersion aspect is often obtained through perceptions of movement and depth in line with the user’s, within the recreated space. The option of headphones and some added spatial sound effects could have pushed this concept further.

The Forum

Cryptoporticus of Nero

Within the Forum, there were a few different musical and audio-visual experiences available. These were mainly positioned within the underground spaces and tunnels, making use of the acoustics there. These seemed available to those who had a greater access ticket, so a fee was paid at the original ticket office instead of at each installation, though no details were given to tell us of these available experiences making it uncertain if they were properly promoted or advertised (when researched online there were only references to audio guides available).

The first installation I witnessed within this site was in a long, damp tunnel, noted as the Cryptoporticus of Nero. A very impressive projected visual display was along one wall, accompanied by a bold and atmospheric composition of ambient string music. The long wall was used like a gallery space, to display other relevant pieces of art in the Forum. The display depicted wall decorations from the houses of Augustus and Livia, changing and moving in a colourful collage, enlivening an otherwise plain and cold underground space of historical significance.

The projectors and speakers took advantage of the layout of the stone tunnel, positioned in the high up dips in the masonry. Because of this, the images were all level and equidistant, and the music extended over the length of the tunnel and completely filled the space. A test recording was made with the zoom H3 VR to try and capture the immersive quality of the installation to refer back to later.

There isn’t anything I felt that could be changed or adapted with this work, as it made full use of the space, the loop of music was of a good length and suited the artistic nature of the projections. Perhaps an addition of sound effects could be tested, but the simplicity in this case seemed effective. The overall installation was seamless and engaging, and in my opinion, a great example of how audio-visual installations can bring dark stone heritage structures to life.

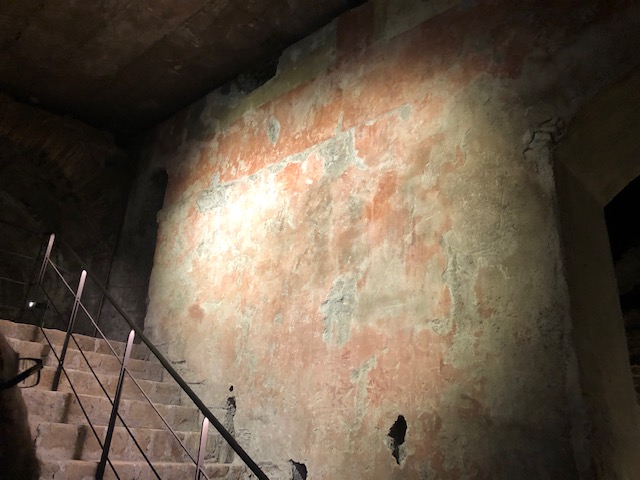

Domus Transitoria

This underground circuit was available as a private tour, given in either English or Italian. The concept of a guided tour containing a series of different immersive audio-visual experiences mixed with a tour guide was new to me in this kind of heritage setting, and felt very innovative. You began the tour by going down steps into a main chamber, and from there the tour guide carrying a tablet began the show. Similar to the Cryptoporticus, headphones were not provided and the natural acoustics of the underground space was used. A narrator introduced the space and the history, creating a story for visitors to follow, which was accompanied by ambient music.

What was also very interesting was the use of blank walls as presentation boards. It was clear this tour was well curated, as the mixture of ‘immersive presentations’, Oculus VR, and a physical tour guide to walk with you and answer questions was very effective. It was only a small group and therefore there was no crowding – it felt personal and there was plenty of space to explore the small rooms.

The second chamber housed the Oculus VR experience, which was presented through wired headsets and simple clear plastic stools to sit on, taking up minimal space and keeping the group together. This experience was again seamless, and the visuals out-did those at the Baths of Caracalla, with a lot more detail given on lighting and colour. Though no headphones were given, the acoustics of the chamber was more than satisfactory to accompany this VR display. Reconstructions were shown of the building like that of the Baths, and the same narrator spoke as in the first chamber. But what was particularly beautiful was the way the rooms came to life, constructed and deconstructed in front of the audience, with flowing water in the fountains. Only voice and music were heard, no sound effects or foley. The final shot was a glorious rendition of the Transitoria from above at dawn.

Another presentation technique was displayed during this tour, that was also used at the last interactive site I visited before the end of my trip – the ‘Santa Maria Antica’. The projected animations on the last presentation in the tour actually used white lines to highlight graffiti and different indentations in the wall it was displayed on. This meant the wall was not only a presentation tool, but displayed as an artefact of interest in itself, further justifying the development of audio-visuals as a useful and unobtrusive engagement tool for augmenting audience experiences of heritage structures.

Santa Maria Antica

My brother had already visited this church within the Forum and noted it as a very exquisite installation for me to visit. Upon entering the church, you are greeted with the sound of sacred choral music, reverberating around the open foyer. This music is less intense than that of the experiences in the underground spaces, as it is just used to create an atmosphere within the church, allowing visitors to walk about without being overwhelmed. The sound levels were also lower so as to balance with the immersive presentations that were being shown in two small side chambers.

These side chambers contained presentations accompanying the wall paintings found inside, but instead of having a narrator speaking over the top as before, only ambient atmospheric music was playing, and small sections of writing flashed about the walls describing what was there. This technique of white lines drawing out and highlighting the figures in all the wall paintings was very effective, as in this case it was used as a tool for completing sections of the art that was no longer there. This gave the audience an opportunity to see the overall picture without intrusive recreations that would modify the archaeology.

Reflections

This concept of immersive presentations was of particular interest to me in relation to my research. This was due to them having similar qualities to immersive audio works; being projected into the space but leaving no trace behind. They highlighted details of the structures, whilst also keeping an overall atmosphere and narrative to each chamber. I believe an immersive audio work within a heritage site would have this similar duality; being both a means for storytelling and atmosphere (narration, acoustics, music), but also a platform for outlining precise details and the uniqueness of the artefact or monument it is linked to (foley or sound effects). Though there was music playing throughout the Forum experiences, I felt that this music didn’t articulate the other elements that the immersive presentations did. It was used for atmosphere, and the only storytelling heard was done through a narrator’s voice. The music was created to emphasise the acoustics of the chambers or tunnels, and give that sense of ‘awe’ that perhaps Forum monuments intend to give the visitor; but it was surprising that with such a knowledge of what was present within those spaces, and the people and activities involved in them, that the soundscapes weren’t more textured or complex, especially when such investment was put into visual VR. The immersive presentations expressed the most depth of thought and engagement, and therefore was most influential to me in my immersive audio research.

In relation to the experience at the Baths, which was quite different from the others, it was clear to me what could be adapted to give the experience greater depth, and what elements might have been lacking in an artistic sense. On a positive note, the ‘VR’ experience was very accessible and popular, and upon observing both older and younger audiences using the headsets, it could be seen that there was little room for error and everyone who had one was using it with ease. When looking at whether the headsets achieved the goal they set out to do, it is likely that audiences would say they did. They very simply and easily depicted the rooms in a clear enough rendering of the space, and gave enough audio to inform the audiences of the history of the monument. There is a lot more that this mobile platform can give, both audibly and visually, but observing the accessibility of the smartphone platform in a heritage context was helpful for my research.